In this series, Grady Hendrix, author of Horrorstör, and Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction are back to uncover the best (and worst) horror paperbacks from the 1980s.

Everybody remembers their first Joe R. Lansdale story.

Mine was “Night They Missed the Horror Show,” which I read in the anthology Splatterpunks in 1991. To say I was unprepared for this black-hearted tale of racist hillbilly snuff-film purveyors and the high-school hellraisers who inadvertently stumble upon their doings is an understatement. Like a sucker punch to a soft belly or a club to the base of the skull, “Horror Show” leaves you stunned, out of breath, a hurt growing inside you that you know won’t be leaving any time soon. Hasn’t left me this quarter-century later. I know Lansdale would have it no other way.

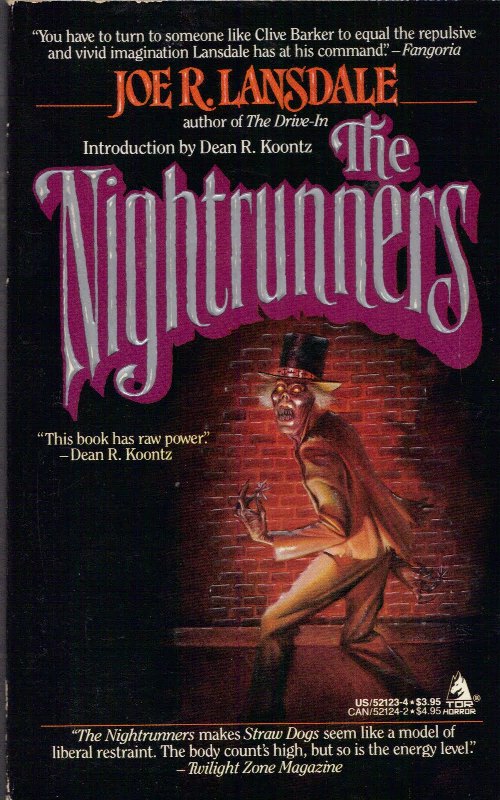

Funny thing was, I craved that feeling. Sought it out. So within a couple months I’d finally tracked down Lansdale’s 1987 novel The Nightrunners (published in paperback by Tor, March 1989). I recall coming home one afternoon from the bookstore I worked at with my brand-new copy, going into my room, locking the door and then reading it in one white-hot unputdownable session. That had never happened to me before; I usually savored my horror fiction over several late nights. But The Nightrunners wouldn’t let go. Lansdale’s skill in doling out suspense and the threat/promise of the horrible things to come is unbeatable. He even tells you flat-out, after quoting a newspaper article about victims of a “Rapist Ripper,” that “no one knew there was a connection between the two savaged bodies and what was going to happen to Montgomery and Becky Jones.” You know you got to keep reading after that!

The Joneses are a young married couple, living in Galveston, Texas, whose lives are shattered when Becky, a teacher, is raped by young men who were once her students in high school. She is haunted by the event, months later, can’t even bear her husband’s Montgomery touch. The nightmares are horrific re-enactments, almost as if her rapists are living in her head. Monty is a pacifist professor and he can’t deal with how ineffectual the crime makes him feel; it throws his entire life philosophy into doubt. Rather than being relieved when Clyde Edson, the teenage scumbag who led the attack and the only one caught by police, hangs himself in his jail cell, Becky is horrified: she’d seen his death in a vision. Monty, with his “sociological thinking,” and a therapist try to explain it away, a result of her trauma, but Becky knows something worse is waiting. Monty’s plan? Take her away to their friends’ isolated cabin in the woods. Surely, they’ll be safe there!

Clyde Edson never named his accomplices, and they are still out there, tooling around the night streets in a black ’66 Chevy, looking for trouble, always first to draw when it shows up. Like a mini-Manson, Clyde drew the disaffected to him, into his poisonous orbit; a crew of violent losers with nothing to lose. His best bud Brian Blackwood, however, is different: together the two of them fancy themselves Nietzschean “supermen” (or, as Blackwood writes in a journal, “It’s sort of like this guy I read about once, this philosopher whose name I can’t remember, but who said something about becoming a Superman. Not the guy with the cape”), ready, willing, and able to topple civilized society and live by muscle and wit, appetite and anger. AKA rape and murder, of course.

Here’s where things get strange: one night Brian dreams, dreams of a god shambling up a black alley “and somehow Brian knew the shape was a demon-god and the demon-god was called the God of the Razor.” Lansdale shifts from his tale of gritty crime and violence into something surreal and grotesque. It is, in its way, absurdly beautiful.

…tall, with shattered starlight eyes and teeth like thirty-two polished, silver stickpins. He had on a top hat that winked of chrome razor blades molded into a bright hatband. His coat (and Brian was not sure how he knew this, but he did) was the skinned flesh of an ancient Aztec warrior… out of nowhere he popped out a chair made of human leg bones with a seat of woven ribs, hunks of flesh, hanks of hair, and he seated himself, crossed his legs and produced from thin air a dummy and put it on his knee… the face the wood-carved, ridiculously red-cheeked face of Clyde Edson.

(You can see that the cover artists—Joanie Schwarz and Gary Smith—actually read the book!) Brian learns that Clyde is possessed by the God of the Razor, and now Clyde is going to inhabit Brian and together they’re going to find Becky and, in Clyde’s charming parlance, “cut the bitch’s heart out.” With the God of the Razor there to guide their hand. With his idiot minions in tow, Brian/Clyde begin their night run, rumbling through the countryside in that black Chevy, laying waste to any and all who get in their way.

I haven’t mentioned the many characters that inhabit the novel, men and women living the hardscrabble Texas country life Lansdale knows so well, using humor and sex to ease pain and poverty. Some of the folks seem like stereotypes but Lansdale always invests a knowing detail into them. He doesn’t belabor characterization, and he knows it hurts the reader more when he hurts characters we care about. The teenagers are irredeemable evil, yes, smart yet deluded or stupid and easily led. Monty continually questions his manhood; Becky struggles to contain her fears and begin a normal life again. Despite the depths of sexual violence that Lansdale plumbs here—and make no mistake, he plumbs deep, disturbingly deep—there is always an element of humanity; he balances his cold steel razor fear with an understanding of people in extreme situations. We can survive, if we fight. And if we can get our hands on a frog gig, all the better.

Don’t get me wrong: The Nightrunners is not a noble book; it is mean, it is nasty, it is ugly as hell in places and it doesn’t flinch, ever. Also, it’s vulgar and crude and clumsy—the less said about a flashback to Monty and Becky’s “meet cute” scene the better—but beneath its exploitative surface beats an energetic heart. In cinematic terms, the novel is kind of a hodge-podge of ’70s and ’80s horror, thriller, and crime entertainment. Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs is the obvious inspiration, I think, but one can also sense Wes Craven and Sam Raimi nodding approval, while the Coen Brothers hang around in the background. Richard Stark and Elmore Leonard peek in every once in a while too. Lansdale likes his humor icy black, a bit corny even, and in the direst of situations. It’s what distinguishes him from a couple other extreme writers of horror from the same era, Jack Ketchum and Richard Laymon. He’s not as dour as the former or as dreary as the latter. Joe R. Lansdale is his ownself, as he’s always said, and I believe him. You will too.

In the years since this early novel, Lansdale has become more and more prolific—and even better at this writing thing. He’s long since moved out of the cult ghetto, winning major awards (2000’s The Bottoms took the Best Novel Edgar Award) and having film adaptations made (2014’s indie crime flick Cold in July, based on his 1989 book). His personal Facebook page is filled with his advice about the writing life. I’ve read quite a few of his ’80s and early ’90s novels and stories (try The Drive-In from ’88, the short story collection By Bizarre Hands from ’89, or Mucho Mojo from ’94) and enjoyed them, but it is The Nightrunners that has stayed with me best: it is pulp ’80s horror fiction at its rawest, most unforgiving, most relentless. Behold the God of the Razor… and don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.